THE FAMILY FEUD

In the early 19th

Century both families had settled in the Tug Valley along the Kentucky-West

Virginia border. The McCoys put down roots on the Kentucky side of a stream

called Tug Fork, while the Hatfields lived on the West Virginia side. By the

time of the Civil War each family was headed by an ambitious and

confrontational man. The McCoy family was led by Randolph McCoy. The patriarch of the Hatfield clan was William “Devil Anse” Hatfield.

Trouble started during the

Civil War; the Hatfields fighting for the Confederacy and the McCoys for the

Union. After being discharged from the Union Army, young Harmon McCoy,

returning home from the war, was hunted down and killed by resentful Hatfield

kin folk.

Purloined pigs, crooked

courts, and rising resentment fueled even more violence. Hostilities peaked in

1882 when three of Randolph McCoy’s sons killed Ellison Hatfield, the brother

of “Devil Anse” Hatfield, leader of the Hatfield family. “Devil Anse”

retaliated by capturing and executing the three McCoy brothers, without a trial

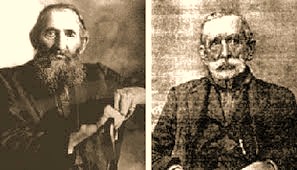

of course, by tying them to a tree and shooting them. The accompanying photo

shows heavily armed Hatfields.

Violence surged and receded

for the next few years. In 1887, a lawyer, the cousin of Randolph McCoy, used

his influence to have the murder indictments reissued against the Hatfield boys

who had killed the McCoy brothers. Their extradition from West Virginia to

trial in Kentucky was slow and frustrating, so the McCoys raided the Hatfield

settlement taking several men captive back to Kentucky for trial.

The Hatfields were enraged

and planned to kill Randolph McCoy. On January 1, 1888, a

party of Hatfield men surrounded McCoy’s home and opened fire on his family

sleeping inside. They set fire to the house killing two of Randolph’s children

and beating his wife, who they left for dead. This has been called the New

Year’s Night Massacre.

Now the conflict expanded.

It was not only between the two families, but between Kentucky and West

Virginia. The Governors of both states called up the National Guard as more

retaliation raids were made by the McCoys into West Virginia. The governor of

West Virginia accused Kentucky of violating the extradition process and took

the issue to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court ruled against West Virginia (and

therefore damaging the Hatfield cause). All eight Hatfield men were found

guilty of murder by a Kentucky jury; seven were sentenced to life in prison and

one was executed for murdering the daughter of Randolph McCoy.

The bloodshed had finally

reached its finale, but the “Hatfields and McCoys” became an American metaphor

for any harsh rivalry.